|

|

|

| |

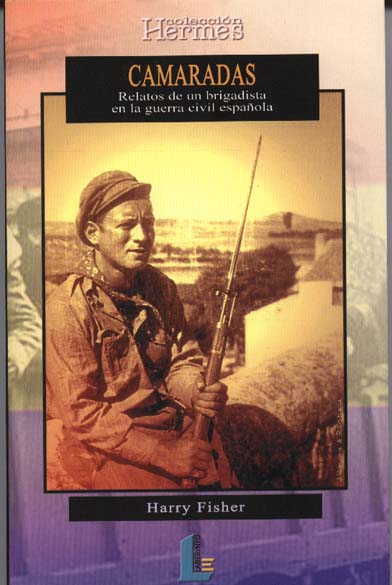

Harry Fisher

was one of about

2,800 U.S. volunteers who went to fight in the International

Brigades during the Spanish Civil War.

The commitment they made there keeps inspiring and

encouraging people around the world to continue the good

fight for a better world, peace, and justice. |

|

|

|

Blood that sings beyond the frontiers

Speech given by Juan María Gómez Ortiz, member of A.D.A.B.I.C.

(Associació d’Amics de les Brigades Internacionals a

Catalunya) to commemorate the 62nd anniversary of the farewell for the

International Brigades.» Barcelona, 28th October,

2000.

Translation to English by Cherry Embury and Jane

Larson, members of A.D.A.B.I.C.

Origins and formation

With the first news of the military rising, Mundo Obrero

of the 18th July 1936 published

a call to all workers and anti-fascists to defend the Republic.

On the same day, Dolores Ibárruri «Pasionaria» was broadcast,

calling to the people of «Catalonia, the Basque country and

Galicia and to all Spaniards to rise in defence of democratic

liberty and conquests.» This call would soon cross the frontiers

of Spain, reaching the most remote corners of the world and would

receive a reply which, by its quantity and quality, would prove

to be the greatest epopee of international solidarity that

humanity has ever known.

Between 35.000 and 45.000 men and women from 53 countries

responded to the call, a third of whom would shed their life’s

blood in Spain. Why such a massive and generous response?

Primarily because the Spanish Republic, since its origin on 14th April 1931, had awoken much

sympathy between workers, democrats, and anti-fascists all over

the world. The Agrarian reform, the vote for women, the halt to

«caciques» and reactionaries, the boost to education, aid for

the unemployed, all of which had brought to a head at a time of

world economic crisis of great intensity -later known as the Depression

of the 30’s- all these were to the humanitarian and

progressive credit of the Republican regime. The victory of the

Popular Front in the elections of 16th February 1936,

which meant a political amnesty for thousands of prisoners who

had been incarcerated since the Asturian Rising in the autumn of

1934, was also received with enthusiasm in a Europe which, since

the 20’s had seen the risen of fascism and dictatorships.

Since the coming to power of the nazis in Germany at the end

of January 1933, the world had witnessed dozens of growing abuses;

the burning of the Reichstag, the detentions of congressmen and

trade unionists, the establishment of internment camps, such as

Dachau on the outskirts of Munich, the promulgation of the

racists laws of Nuremberg and the systematic persecution of Jews

plus the growing attitude of superiority in international

politics were all viewed with preoccupation and alarm by

democratic powers. The Japanese in Manchuria, the Italians in

Ethiopia and now the Nazis, re-arming and establishing themselves

in a racist, police state. Meanwhile, what were the democrats

doing? Practising what could be called «pacific politics»,

which the mass of workers and democrats perceived as timorous

concessions to the dictators.

Thus when Spain presented what was clearly a fighting front

against world fascism –for it soon became apparent that Franco

was a pawn and not only the Spanish oligarchy but the Berlin-Rome

Axis which supplied men and material from the outset–

the antifascists of the world understood that it was time to stop

in their tracks those who wished to assassinate liberty in Europe

and the world.

In the summer of 1936, Paris was converted into the principal

refuge for political exiles from central and Eastern Europe.

Democrats, anarchists, socialists, communists, tradeunionists,

Jews –all had arrived in the French capital, fleeing Nazi

barbarity. Some of these men and women were to come to Barcelona

to participate in the Popular Olympics, under the honorary

presidency of the President of the Generalitat, Lluís

Companys i Jover. These has been devised as the

counterpoint to the Olympic Games in Berlin, about to take place

and which had been planned as a publicity platform for its regime,

by the Nazi hierarchy.

In Barcelona all was prepared to receive the anti-fascist

athletes, the games were to be opened on Sunday 19th

with a series of cultural and sporting events. Many of these men

and women, instead of competing in the stadium, would be caught

up in the fight, such as the Italians Fernando Rosa (socialist,

killed on the Guadarrama front in September) or Nino Nanetti,

communist who joined the Octubre Column. That same Sunday

19th of July, the Austrian athlete Mechter was

killed, the first International killed in Spain. Jews figured

amongst the first anti-fascists volunteers. The Spanish Republic

had opened its doors to welcome Jews and in 1935 had received

2000 of them. The Thälmann group was organised in

Barcelona, made up of Jewish refugees, including women volunteers,

and led by Max Friedeman, one of the first to join the

fight. This group was the embryo of the Thälmann Column

whose members by August they were already fighting in the

Tardienta sector. Ernst Thälmann was the secretary of the

German Communist party imprisoned since March 1933 in

Alxanderplatz prison in Berlin, to be later sacrificed in

Buchenwald, 18th August 1944.

Hans Beimler, communist ex-congressman in Reichstag

escaped from Dachau after a particularly brave adventure and on

arriving in Spain, took immediate political charge of the German

combatants, on the sector of the road to La Coruña, 1st

December.

From the first days of the conflict there was a constant flow

of Frenchmen, Belgian, British and others, across the Pyrenees.

The English Felicia Browne, killed on the Aragon Front, 25th

August, was the first woman to be killed fighting. The brilliant

student and poet John Cornford, killed in December on his

21st birthday, were among the youngest casualties

among the British. This people soon acquired the fame of forming

the first barricade against the fascists advances with their

bodies. The mature Arnold Jeans, the railway man Martin

Messer, the communist organiser James Kermode, the

young Scotsman Jimmy Hyndman to name but a few of the

fallen. The British also required a reputation as excellent

machine-gunners, so that the Tom Mann Centuria was formed

in the Pedralbes barracks would supply machine gunners for the

first battalions of the Internationals.

The first International Brigades

The Commune de Paris battalion entered into battle in

August, in defence of Irun and was composed of Frenchmen,

Belgians and some Britons. Jules Dumont commanded them and

Pierre Rebière was the political commissar, who, years

later was to become one of the heroes of the French Resistance.

The numbers of Volunteers grew and it become evident that this

wealth of solidarity must be structured and organised. If, during

the first weeks, many leaders of the Socialist and Communist

Internationals were confident that the Republic could quickly

crush the insurrection by its own means, it soon became evident

that the massive nazi-fascist aerial support given to the rebels

would make their defeat more problematic. This help made possible

their rapid advance from Andalucia up to Extremadura, towards

Madrid. Different organisations began preparations for that which

had started as a great movement of international solidarity

should become, using a graphic expression of that time, «to

convert endeavor into steel.» These organisations included the Comitè

d’Aide au Peuple Espagnol, leaded by the philosopher and

historian refugee living in Paris, the Jewish Hungarian Victor

Basch (later, with his wife to perish at the hands of the Gestapo)

and the Komintern.

The actions in Madrid by outstanding members of Spanish

communism such as Pasionaria and internationals such as André

Marty or Palmiro Togliatti, were met by parallel

action in Paris. To name several, Luigi Longo (Gallo)

who, years later (in 1964 at the death of Togliatti)

became secretary general of the Italian communist party; the

Polish Karol Swierczevski (the future General Walter);

the German Gustav Regler and the Czech Klement Gottwald

(later president of his country in the post-war years). Number 8,

rue Mathurin-Moreau in Paris, headquarters of the Maison des

Syndicates, had never known such a fervour of organisation.

It negotiated to create a complete formation of an International

Brigade, endowed with its own campaign equipment and armament. It

fell to the German communist Willy Münzberg to organise

supplies and lorries of arms, food and clothing soon began to

arrive. The Italian communist Giulio Cerreti, «Allard»,

was responsible for the technical directions and in view of the

rapid advance on Republican territory by land and sea, speedily

established offices and centres in southern France, in Perpignan

and Marseilles.

Meanwhile, in Spain, from the 4th September, Francisco

Largo Caballero was president of a government that included

the C.N.T., but whose systematic lack of confidence towards the

communists made him little pre-disposed to accept the idea of the

creation of an international contingent, in which it supposed

that the Kommintern would be involved. However, the

military commanders of the Republic saw it quite differently. At

the outset, they asserted that they only needed qualified

technicians, perhaps due to the lack of armament of the

volunteers. But when the organisers of the Brigade assured that

they were almost autosufficient thanks to the international

clandestine network of arms dealers and particularly when soviet

arms began to arrive with the Zirianin at the end of

September, the Spanish military leaders could only accept with a

sincere welcome, the much needed help. The foreign fighters who

had already received their baptism of fire in Spain quickly

earned a reputation of bravery.

While recruiting was taking place in all French communist

party offices and trade unions, Luigi «Gallo» was

in charge of establishing a reception centre in Catalonia on the

Spanish side of the frontier. With the help of the P.S.U.C.he

managed to procure the former military fortress of San Fernando

in Figueras. An in Madrid he also made a move to establish a

centre of instruction for the Brigade in Spain. That the

Republican state could legally establish the admission of those

foreigners would, curiously enough, be solved by a law of the

monarchy. Sure enough, a year later, with Indalecio Prieto

in the Ministry of War in Valencia, a decree was published

establishing the situation of the International Brigades in the

bosom of the Spanish people’s army, saying in its first

article «to substitute the former unit of foreigners, as formed

by decree of 31st August 1920,

the International Brigades are created as units of the Spanish

Army». Diego Martinez Barrio, parliamentary president,

acquired installations in Albacete as a reception centre for

international volunteers. One of the building was the former

barracks of the Guardia Civil in this city from La Mancha, with

still visible signs of the early days of the uprising in its

walls.

No sooner at Albacete than André Marty had organised a

committee to take charge of the volunteers who were to arrive.

Along with Longo and Togliatti (known as «Alfredo»),

the committee also comprised Mario Nicoletti, Pietro

Nenni and Francesco Scotti, former secretary of the

communist party in Milan.

On the 13th October the first volunteers arrived

from Alicante where they had arrived the day before on a ship

from Marseilles. The first three battalions were formed on 22nd

October; the afore-mentioned Commune de Paris (made up of

Frenchmen and Belgians), the Edgar André Battalion (led

by Hans Kohle) which had taken its name from an anti-nazi

who had been be-headed in Germany, and the Italian battalion made

up of the remnants of the former columns Gastone Sozzi and

Giustizia i Libertà. This unit was led by Randolfo

Pacciardi, a liberal republican who, far from being communist

was, in the 50’s, several times Minister of Defence in

various centre-right governments. This new unit was called the Garibaldi

Battalion. Meanwhile, volunteers continued to arrive in their

hundreds, making up a forth battalion, the Dombrowski, led

by the Polish Tadeusz Oppman. It was mainly made up of

Polish, but also included Czechs, Yugoslavs, Ukrainians and

Bulgarians. As with all battalions there was a notable percentage

of Jews. All these units formed the 11 Brigada Mixta, also

known as 11 Brigada Móvil, Primera Brigada

Intrnacional or XI Brigada Internacional, and were led

by general Emil Kléber (Manfred Zalmanovich Stern),

a communist from Bukovina with experience in missions for the Komintern

in China and other places. Nicoletti was the political

commissar, known as Giuseppe di Vittorio in Spain.

On the 29th October it was transmitted in French (official

language of the International Brigades) that the 4.000 brigaders

in Albacete would be re-distributed to the towns in the province

of Albacete, to make the task of training easier. The Edgar

André was sent to Mahora; the Commune to La Roda, the

Garibaldi to Madrigueras and the Dombrowski to

Tarazona de la Mancha. Today in all these towns there is an

important movement for the recuperation of the historical memory,

in the conviction that is part of the cultural patrimony.

On 4th November the XI Brigade was preparing to

leave Albacete to combat the rebels advance on Madrid. At the

last moment the Garibaldi battalion was withdrawn to form

the nucleus of a second International Brigade. On 5th

November the XI left Albacete with 1900 men and arrived at

Vallecas. On 6th November the political commissary of

Albacete received the order to dispatch a second Brigade to the

Madrid front by the following day at the latest. A second force,

comprising approximately 1600 men and including the Garibaldi,

Thälmann (led by Ludwig Renn with Beimler

as political commissar) plus the French-Belgian and André

Marty battalions, was sent to Madrid on the 7th.

This would become the XII Brigade and was under the command of general

Lukacz (in reality Matei Zalka, later killed in combat

in 1937, a shell hitting his car while he was inspecting the

Aragon front). Luigi Longo was the political commissar.

Baptism of fire in Madrid

The International’s baptism of fire took place in the

defence of Madrid, under the command of General Miaja,

responsible for the Defence Council of the city. The rebel General

Varela’s troops attacked across the Casa de Campo and

Toledo bridge. On the morning of the 8th November,

there was a general sigh of relief and people’s skin

prickled with emotion and pride at the passing of the diverse but

orderly troops at they passed by the Gran Via. At the end of the

Gran Via the Internationals took up positions, the Edgar André

battalion in the University Campus, the Commune de Paris

in the Casa de Campo and the Dombowski in the Manzanares

river. Kléber established his headquarters in the

Philosophy Faculty in the campus. The XII Brigade was sent to the

south of the city, towards the Cerro de los Angeles. And later

between the hippodrome and the Puerta de Hierro. The Thälmann

battalion was sent to the Moncloa palace gardens. On the

university campus (built during the last decade under the

auspices of the Canarian physiologist don Juan Negrín López),

the rebels had taken the School of Architecture, the Clinic

Hospital, the Agriculture School and the Casa de Velazquez. The

loyalist held the Faculties for Sciences, Philosophy and Medicine.

The battle lasted two months with hardly a pause. In the first

month the XI suffered 900 death casualties and many injured. In 3

weeks the XII lost 700 men.

Re-organisation started on the 3rd December, taking

linguistic factors into consideration. The German speaking Thälmann

was transferred to the XI and the Dombrowski joined the

XII. In the middle of January the XI was pulled out of the first

line of the front and sent to rest in Murcia. Since entering into

combat on the 8th November the XI had lost

approximately 1.230 of their original members and was now

estimated to made up of 600 survivors of 3 battalions.

The XII Brigade was finally formed by the 11th

November, originally with Slav and French volunteers, although it

was represented by many nationalities. It was under the command

of the German communist Wilhelm Zaisser (general Gómez)

who had received training in the Frunze Military Academy

of the USSR It consisted of the 8th battalion, the 21

Nations or Tschapáiev (named from a Soviet guerrilla

leader of the civil war), the Henry Vuillemin and the Louise

Michel. In the company one of the Tschapáiev there were

Germans, Swiss, Czechs and Jews from Palestine.

The XIV Brigade was organised just before Christmas 1936 under

the command of Karl Swierzewski (general Walter)

who, like Zaisser, had studied in the Frunze. It

included 4 battalions of about 750 men in each: the 9th

or Nine Nations (Italians, Yugoslavs, Germans and Polish),

the 10th or Marselleise (French),

the 12th of French, British, Irish and

Argentineans and the 13th of Frenchmen.

The XV Brigade was formed in Albacete on the 9th

February 1937. It was made up of the battalions 8th

February, Dimitrov and British. Shortly after

the Americans arrived, the last but not least contingent to

appear with nearly 3.000 men, a third of who would be buried «with

the Spain’s earth as shroud.». They were grouped into the Abraham

Lincoln battalion. Later it was formed a second

American battalion, the Washington, that after the severe

casualties in action, was finally associated to the Mackenzie-Papineau

battalion, made mainly with Canadian volunteers. A number of

Cubans joined the Lincoln battalion although Cubans had been

fighting since the battle of Madrid, including the poet Pablo

de la Torriente Brau, killed at Majadahonda (the Madrid front)

in November 1936. The first contingent of Americans to arrive in

Spain consisted of 96 men who had left New York in the SS

Normandie, arriving in Spain on New Year’s Day. The

French-Spanish border was then closed in accordance with the Non-Intervention

Committee, so the men had to enter Spain with the help of guides

after an exhausting crossing of the Pyrenees from Perpignan until

their arrival in Figueras. Here they received several days of

training until a convoy was organised which, after several days

of travelling by train, brought them to Albacete and from there

to Tarazona de la Mancha and Madrigueras or Villanueva de la Jara

in the province of Cuenca.

Today we don’t have the time to enumerate, not even

briefly, the combat actions in which the International Brigades

participated. It’s sufficient to say that they were in all

operations of the war, and were always used as shock force, be it

for attack, counter attack or defence. Let us cite a few of the

principals operations and battles where they made history and

legend:

In the defence of Madrid, in Mirabueno (Sigüenza), Teruel and

Lopera, all in 1936. In Motril, Pitres and Jarama (February 1937),

Guadalajara in March; Pozoblanco and Pingarrón in April.

Garabitas and Utande in May. In Huesca in June. The battle of

Brunete took place in July of 1937, in which four of the five

Brigades participated. In the summer of that year took place the

battle for Zaragoza, with the actions of Quinto, Villamayor de Gállego,

Belchite, Mediana, Grañén; and in the autumn Fuentes de Ebro,

Cuesta de la Reina. In the battle of Teruel in January of 1938.

In Segura de los Baños and Zalamea, in the Extremadura front. In

those which were called retreats but in reality were numerous

battles which attempted to stop the massive Nazi-Fascist

intervention which finished by cutting the Spanish republican

territory in two. Again Belchite, Híjar, Caspe, Maella, Batea,

Gandesa, Lleida, Mora d’Ebre. And finally the battle of the

Ebro, from Santiago’s day in 1938: Amposta, Ascó-Flix,

Corbera de Terra Alta, Gandesa, Serra de Pàndols, Serra de

Cavalls and Vértice de Puig Gaeta, in which the 5 brigades

participated.

General Juan Modesto, chief of the Ebro Army, awarded

the bravery medal to each one of the 5 brigades. The Lincolns,

Garibaldi, Rakosi, Zwölfte Februar and Vaillant-Couturier,

wrote pages of heroism defending en reconquering hills, the most

famous of all known as Death Hill. A battle so tough that the

memory of it greatly moved commander Antonio of the

Republican Air Force who, on the 14th October in

Corbera de Terra Alta at the unveiling of the monument in honor

of the dead of the I.B.’s in the battle of the Ebro,

affirmed that from the air it was impossible to see Serras de Pàndols

or Cavalls, for the dust made by explosions. And below this dust

was the infantry of the Republic, enduring rock grape shot. The

23rd September was to be the last day that the

brigades fought. Commander Sagnier and Commissar Henry

Rol-Tanguy of the XIV Brigade concluded the last attack of

the Internationals, who at the end of the day were relieved for

those «political and State reasons», that Dolores invoked

a month later in her farewell speech. And if was for no-one else

that the President of the Council, Doctor Juan Negrín López

in his discourse before the General Assembly of the Society of

Nations invoked:

|

| «The Spanish Government is disposed to

eliminate what ever pretext could continue to

doubt the national character of the cause for

which the Republican Army fights». |

|

At that time the Brigades only represented a minority

disseminated in the popular army, which in the battle of the Ebro

represented hardly 5% of those involved. This is one of the

themes, that has lent itself to dispute. Not only for the old «Polibius

effect»for which the number of the opposing forces is

exaggerated with the aim of giving more merit to one’s own,

and which has caused the disqualification of claims made by

historians on Franco’s side. But also for the actual

nature of the Brigades –don’t forget that from 16th

January 1937 the Non-Intervention Committee, with headquarters in

London, declared recruitment illegal as well as the sending of

volunteers- it was extremely important at that time to maintain

secrecy in many aspects related to the arrival and entry into

combat of the internationals.

Nazi-fascists naval intelligence agents infiltrated Paris,

Perpignan and Marseilles, and their information concerning troop

and arms movements established the objectives for the submarines

of the Axis. As an example, we can cite the sinking of the City

of Barcelona in the spring of 1937 in which many of its

passengers died, the majority of whom were young men coming to

join the Brigades.

There are also those who try to short the figures because they

defend a certain hypothesis, such as that the International

Brigades were a creation of the Komintern, or that set quotas

existed in the different communist parties. Also there are those

that quite simply tried to dull the shine of that unrepeatable

epopee of brotherhood and heroism which were the International

Brigades, to quote Lluís Martí Bielsa, president of the

ADABIC. An epopee that will always be a baggage of credibility

and honesty for the forces that defend progress, peace and

humanity throughout the world.

Colonel Louis Blésy-Granville, former commissar in the

XIV Brigade and president of the Association of Volunteers in

Republican Spain, on the 14th October in the

aforementioned unveiling of the monument in Corbera de Terra Alta,

work of José Luis Terraza, cited figures that range

between 37.000 and 50.000 volunteers, with the possibility that

both figures are slightly high. But the study of this figures is

an interesting exercise, though academic. The question is that

the casualties suffered by internationals were so widespread that

a progressive «españolización»of the Brigades was necessary

such that in the summer of 1937 between 60-70 % Spanish men where

thus incorporated.

This responded to what the International Brigades tried to be,

an integral part of the Spanish Republican Army, without

pretensions of notability. The hispanicizing can be seen in

publications, notably in the paper «The Volunteer for Liberty»,

that from the middle of 1937 inserted more and more articles in

Spanish so that a year later it was practically bi-lingual. In

preparing for this lecture I have carefully examined a number of

English issues of the International Brigades « The Volunteer for

Liberty» which permits one to appraise the second of the aspects

decisive when speaking of the organization and action of the

Brigades, the political aspect.

In imitation of the Red Army and taking up working class

traditions which go back to the Paris Commune –that fight

for history in which the three-pointed star, symbol later to be

adopted by the International Brigades, first appeared- military

and political aspects were intermingled. The commissars first

missions was to explain the need to fight, transmitting the

values which became the cause for the Spanish Republic «in the

cause of all advanced and progressive Humanity ». The commander

and the commissar must always be united and be the first to

advance. The Commissar Inspector General of Brigades, Luigi

Gallo, titled one of his articles «Our International

Brigades, integral part of the Spanish People’s Army », and

compared the brigaders, in his numerous articles, to the soldiers

of year II, whom, in accord with «The Marselleise », extended

the ideals of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity that the working

class now took up with renewed refrain.

In June 1937, about to incorporate new replacements to the

files who would shortly be sent to all brigades, the «Comisariado

General» ordered all the political commissars who were to

receive the new soldiers, to include in their first act the

explanation of the following questions:

-

- What is the Governmental People’s Army fighting for?

-

- Why are the generals and the uprisers against the

government?

-

- Why are the peasants in favor of a Popular Front victory?

-

- Why are the workers defending the Republic against

fascism?

-

- Why is our war a war of national independence?

At the same time it should be explained to the soldiers why

good military training and iron discipline were necessary.

Discipline that as explained by American Captain Alan Johnson,

one of the most valued military instructors of the Brigades, was

not only obeying orders to the letter with the least lost of time,

but also using that time with the best flexibility, good

judgement and initiative. The commissars were o make a list of

illiterate recruits and organize literacy classes.

In the binomial man-arms, by which one measures the

correlation of forces in a war, it was soon clear that the arms

factor favored the rebels in a determined way, who counted on the

massive support of invading forces endowed with the most modern

means of warfare. They disposed of well-trained soldiers,

military professionals from well-equipped units. They had

absolutely no consideration for the civilian population who had

to face, for the first time, the terrible psychological arm of

indiscriminate aerial attacks, as in Malaga, Guernica, Durango,

Granollers, Barcelona and many other places. The battlefields

were converted into laboratories of new arms and tactics which

the Wehrmacht were to use in the war which was to follow:

maneuvers involving tanks, spiral descents of Heinkel III

to machine gun or bomb, the systematic violation of ambulances

and hospitals, which were indiscriminately bombarded, the

shooting of any political commissar captured in battle, a nazi

instruction which would later be used with the same exactitude in

the Ukraine, Bielorussia and the Baltic campaigns. Faced with all

this, the Republic had to build up an army from practically

nothing, with an air force that was known as the Krone Circus

at the beginning. However, at the end of the war it was known as

«The Glorious.»

Peasants, hairdressers, office-workers, servants, school

teachers, waiters, mechanics and «banderilleros» from the

outstart the men who made up the Popular army had to wait in

trenches for someone to be injured in order to procure a gun.

Amongst the foreign volunteers was a contingent of workers,

students, sailors, shop workers, not a specialized military force.

What is more, the majority had no previous military preparation.

Therefore potential must be given to the man-factor, to make all

understand that arms are not invincible if not used in a just

cause, that the best trained soldiers could not defeat

creativeness, tenacity, courage and team spirit. «The

internationals For Liberty demonstrate that the road to victory

is by Antifascist Unity» wrote André Marty.

The pairing commander-commissar symbolised the unity between

the army and the people. For this reason the publications of the

Brigades mentioned the effort of the rearguard to supply the

front. In one report a steel foundry in Madrid was visited and

the women were carrying out traditionally masculine jobs was

emphasized. The women produced bullets, wove protective garments

for the soldiers, distributed powdered milk for the more than 10.000

babies under 12 months that there were in Madrid in September,

1937, and whose mothers had top priority in receiving this milk,

as well as sugar and flour. The International Brigaders were also

concerned about Spanish children and had organized several

welcoming homes, such as Novelda in Alicante.

With this they responded to the affectionate love that they

always received from the Spanish people. The North American Harry

Fisher, transmission runner in the Lincoln Battalion, who

recently visited our country, wanted to visit Madrigueras again (in

Albacete) because he had this small town of La Mancha engraved in

his heart all his life. An orphan since childhood, when he

enlisted in the Brigades and was sent for training in Madrigueras,

he found there for the first time in his life a family that

adopted him and made him feel the warmth of belonging somewhere.

Due to the difference of languages they could hardly understand

each other and when he went to have dinner or brought clothes to

be laundered, he had to speak with gestures or pausing at length

to look up words in a dictionary.

But he will never forget that the Spaniards didn’t let

him go hungry, not him nor any of his young comrades. Although

they had to take it out of their own mouths, dinner for the IBers

was never lacking on those farmers’ and peasants’

tables. They were brothers who had arrived from beyond the

Spanish borders. And permanents linkings were formed between

diverse groups and units of the Brigades. Lagasca Secondary

School in Madrid linked with the XV Brigade.

Special mention is deserved by the injured. The Socorro

Rojo Internacional stands out in the organizations of their

care, as well as a group of self-sacrificing doctors, with

special note given to those who came from the Americas.

Mentioning a name when speaking of the International Brigaders

implies not mentioning others. It must be understood that each

name represents dozens of others who were equally heroic. I’ll

begin by citing the name of the surgeon from New York, Doctor

Edward Barsky a man who was deeply loved by all the

Spaniards, North Americans and all IBers who knew him. He came

from Beth Israel Hospital in Manhattan. He was the first

to volunteer, imitating many of his nurses. More than once he was

surprised by an aerial bombing while he was operating –whether

in a mobile surgical unit or in a country hospital- all of which

were under the control of doctor Irving Busch. Some words

from Doctor Busch will give us an ideal of the

organizational capacity of the First Aid Department of the XV

Brigade:

|

| »We must be prepared to set up a field

hospital of seventy five beds with a complete

staff of thirty personnel. This includes doctors,

nurses and varied types of help so that a

complete hospital unit could be established in a

building as close as possible to the front, ready

to receive patients and ready to operate within

twelve hours after the selection of a site. |

|

The medicine practiced in the Brigades was in the vanguard of

the era and here the first blood transfusion on the front line

took place. Specifically on the road from Almería., where the

Italian aviation sprayed terror among the refugees who were

fleeing from the barbarian revenge that the Italian fascists were

spreading in their way to Malaga. The medical team of the

Canadian doctor Norman Bethune was in charge. After Spain,

Bethune went to China where he died working as a doctor

with the Popular Liberation Army. Some young doctor from

Barcelona were also with the Ibers, such as doctor Moisés

Broggi i Vallés, for whom it is impossible to be with us

here today…But were would like to return the hug he sent to

the Association of Friends of the International Brigades in

Catalonia on the 62nd anniversary of the farewell.

Because the farewell finally came. After having crossed the

Ebro and having put into practice the maxim of Captain Alan

Johnson –that what infantry conquers with the bayonet

must be maintained with the pick and the spade. After having

united in Gandesa, in La Fatarella, in Corbera, in Pàndols, in

Cavalls with the motto «fortify is conquer», came the time of

farewell. All knew that they were leaving behind a Spain that

would suffer a lot. Bilbao was already a German colony. Those who’d

passed through Zaragoza brought news of a harsh repression. Ilya

Ehrenburg described the slaughter in Malaga. In Extremadura

the guerrilleros, those clandestine fighters against fascism,

still resisted. Perhaps there was still hope. For this reason so

many had died. Not only the most famous like Hans Beimler,

General Lukacz, Robert Merriman, Dave Doran,

but also the anonymous ones, among whom we will cite a few

commanders and battalion and Company Commissars like John

Cookson, Pierre Akkermann, Charles Goodfellow, Cazala,

Francisco Parra, Roll d’Espinay, Pierre Brachet, Ivan Ivanov

Paunov «Grobenarov», Vukasin Radunovic, Dorda Kovacevic, Gustav

Kern, Libero Battistelli, René Hamon, Dario Lentini, Renzo Giua,

Al Kaufman, Melvin Ofsink, Tom O’Flaherty, Jack Shirai,

David Reiss, Nilo Makela, Joe Dallet, Leo Gordon, Tadek Ajzen,

Jan Tkaczow, Adam Lewinski, Jaro Tarr, Dusan Petrovic, Gabriel

Fort, Emile Schneiberg, Silvio Belloti, Georg Eisner, Louis

Schuster, Gustav Kern, Casimir, Lambo, Gerhard Kruse, Rasquin,

Laudigon, Boheim, Torralba, Marcel Fromond, Oliver Law,

Max Krauthamer, Butch Entin, Jack Corrigan, Lou Cohen, Rudy Haber,

Aaron Lopoff…

The commander of the XV Brigade, lieutenant colonel José

Antonio Valledor at the military farewell of October 1938

said to his men:

|

| »Your countries may well be proud to have

sons such as you. Sons who put their lives in

jeopardy a thousand times, who shed their blood

on the soil of our beloved Fatherland in order to

help a people who, not wishing to be exterminated,

had thrown all his sons into the struggle: a

people who preferred to die fighting rather tan

live enslaved. (…) Brother

Internationals!

Before leaving for your countries accept

once more the warm embrace of your Spanish

comrades. Live satisfied and proud of the

sacrifices you have made for the Independence of

our Fatherland and for Liberty and Democracy the

world over. And you may rest assured that we, who

remain fighting for universal justice on the

Republican fronts are ready to come to the aid of

your people if at any time they should be

threatened by despotism or servitude.

|

|

On October 29, 62 years ago tomorrow, the general Farewell to

the Brigades took place in Barcelona, before the principal civil

and military authorities of the Republic and an enthusiastic

crowd, grateful and aware of the significance of that act. Some

of those who are here today lived that experience directly and

remembers the banners, the bouquets of flowers, the enthusiasm of

the Barcelona citizens who were paying homage to those heroes.

And they remember those words of La Pasionaria, which

history has chosen to repeat many times and which are engraved in

stone:

|

| »You are history. You are legend. You are the

heroic example of democracy’s solidarity and

universality. (…) We shall not forget you,

and when the olive tree of peace puts forth it

leaves again, entwined with the laurels of the

Spanish Republic’s victory – come back! |

|

They left feeling sadness for not having been able to resolve

the conflict and knew that the Spanish people would have to

suffer. The clamor for victory and guitars with which lieutenant Miguel

Hernández waited the birth of his son had to be changed for

the cradle of hunger cited in his «onion lullabies». The

hopeful trenches of Madrid for a cell in Alicante’s jail.

The bull rings used for fiestas and meetings converted into

places to spend your last night on earth. Hundreds, thousands of

executions, some very significant like that of Martyr

President Lluís Companys, whose death and resurrection Pablo

Neruda sang about. But in Europe the same fascism which had

re-conquered Teruel from the Republic «exclusively by the

Italian-German artillery and aviation», using Doctor Negrin’s

words, profaned the waters of the Seine and Prague the Beautiful,

and broke Greek stalactites and trampled the sacred soil of the

Soviet Union. Spain had only been the beginning; fascism had

prepared a terrible holocaust for Jews and gentile.

The Spanish republicans had the opportunity to put in practice

the words of Major Valledor and help the French in

their liberation. And the International Brigaders made their

lives into a permanent renovation of their commitment to fight

for liberty and democracy, as the hymn of the Thälmann

goes:

»I left my homeland, to Spain I promised

that she would always be free.

They knew how to always wear these three colors of Spain in

their hearts. Although their commitment was to be in many cases

more a source of problems. In the US they were proscribed,

harassed, lost their jobs, accused of spying. Having helped Spain

became an oppressive burden and was brandished as evidence

against the Rosembergs, against Robert Oppenheimer,

against Steve Nelson, against Alvah Bessie, against

Paul Robeson. Doctor Barsky was locked up in the

federal prison of Danbury, Connecticut, for refusing to give Nixon

and MacCarthy’s House on Un American Activities

Committee the names of people who had economically helped the

families of political prisoners in Franco’s jails.

I’ll stop now. Years passed and the time for remembering

arrived. There were visits in 1978, 1986, 1988, the timid

recognition of Spanish citizenship for the IBers that were still

alive in 1995, the visit in 1996 and the one in 1998. But now it

is time not only for remembrance, but for the glory that the

International Brigades, their members, their heroic deeds, their

children and grandchildren that is due to them is adequately

recognized.

Permit me, having paraphrased verses of Miguel Hernández

and Pablo Neruda, to finish with a few from his book «Spain

in the Heart» selected from his poem «Arrival of the

International Brigades in Madrid»

Brothers who from now on

your

purity and your strength, your solemn

history

may be known by child and man, by

woman and elderly,

may it reach all beings who are

without hope

may it descend the mines with air

corroded by sulfuric steam

may it climb the inhuman stairs of

slavery,

so that the stars and all the

spigots of Castille and the world

write your name and your harsh

struggle

and your victory strong and earthy

like a red oak.

Because with your sacrifice you

have given rebirth

to lost faith, the absent soul, the

trust of the earth,

and because of your abundance, your

nobleness, your deaths

like a valley of hard rocks of

blood

passes an immense river with doves

of steel and hope.

Juan María Gómez Ortiz

Barcelona, October 28th, 2000.

BACK TO TOP OF PAGE

|

|

Click on the book

for your language

(English)

(German)

(Spanish) |

|